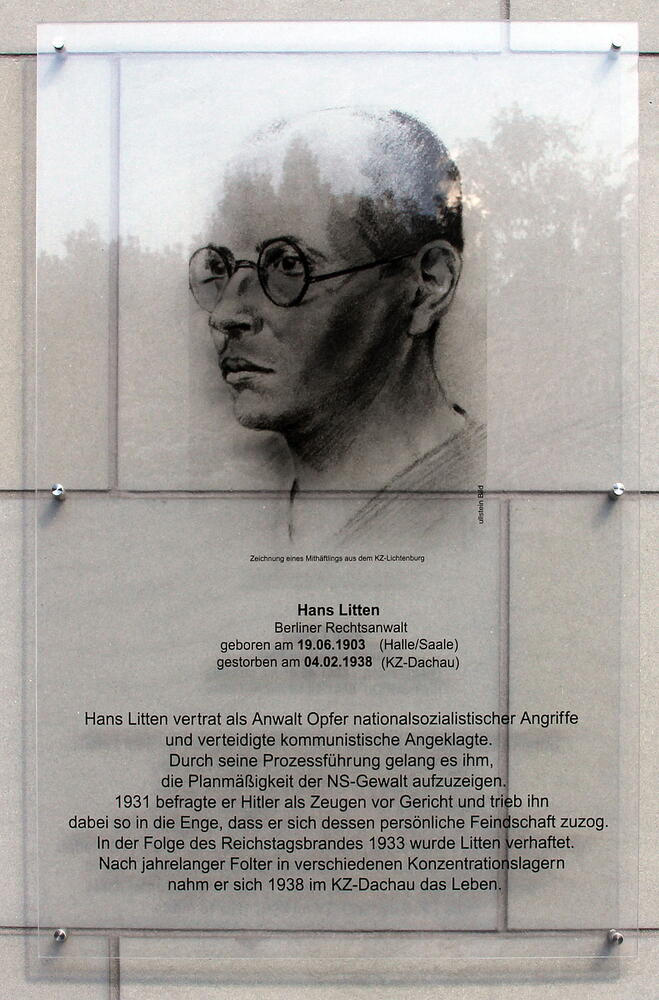

Hans Litten was one of the most courageous figures in the legal resistance to Hitler. Born in 1903 in Halle and raised in Königsberg, he became a prominent lawyer known for his unflinching opposition to National Socialism – most famously when he summoned Adolf Hitler to testify in court during the Edenpalast Trial of 1931. Litten’s defiance would cost him dearly: he was arrested after the Reichstag fire in 1933 and died in Dachau in 1938. In recent years, his story has gained renewed public attention – thanks in part to the television series Babylon Berlin, where the charismatic Litten is portrayed by actor Trystan Pütter.

Knut Bergbauer, a social pedagogue and researcher at the Technical University of Braunschweig, has long studied the Jewish youth movement, the history of labour activism, and forms of resistance to Nazism. In 2022, together with Sabine Fröhlich and Stefanie Schüler-Springorum, he published Hans Litten – Anwalt gegen Hitler (Hans Litten – Lawyer Against Hitler), a compelling biography of this remarkable man. He spoke to Lutz Vössing about Litten’s life, legacy, and political awakening.

How did you come to study Hans Litten?

Almost by accident. I already knew the name when I came across a file on the Schwarzer Haufen – the ‘Black Gang’, a radical youth group. That discovery led me to the writings of Max Fürst, one of Litten’s close friends. Through Fürst’s sister Margot, who was also very close to Litten, I gained access to new material and contacts. The idea for a joint biography came out of an exhibition on the Schwarzer Haufen that I curated with Stefanie Schüler-Springorum. At that point, Sabine Fröhlich – who was researching the figure of the ‘Littologist’, someone deeply devoted to the study of Litten – joined the project.

What was Hans Litten’s background?

He grew up in an upper-middle-class academic household. Born in Halle in 1903, he was raised in Königsberg, East Prussia. His father, originally born Jewish, had converted to Christianity in order to pursue a prestigious legal career. He eventually became Dean of the Law Faculty at the University of Königsberg. His mother, Irmgard, came from a Protestant academic family and leaned more towards liberal values. It was likely through her and Litten’s maternal grandmother that he and his siblings developed a strong interest in literature and the arts.

How did that background shape his political outlook?

There’s not a great deal of direct testimony, but the break with his father seems to have been a defining moment in Litten’s political evolution. His father’s careerism, his physical and emotional absence during the First World War, and his authoritarian nature left their mark. In response, the young Litten began looking for alternatives – rejecting the elite school he attended, joining the Jewish youth movement, and embracing the anti-authoritarian values of the broader youth movement. That search for new horizons laid the foundations of his later political commitments.

Litten was part of the ‘Schwarzer Haufen’ youth movement. What was this group, and what influence did it have on him?

Litten first encountered the youth movement through the Jewish Youth Association in Königsberg, where he met his close friend Max Fürst. That local group soon became part of the Deutsch-Jüdischer Wanderbund – Kameraden, the largest non-Zionist organisation within the Jewish youth movement. But the question might be better reversed: what influence did Litten have on the Schwarzer Haufen?

Together with Fürst, Litten founded the Schwarzer Haufen in the mid-1920s. Their aim was to inject political awareness into what had largely been an apolitical youth league. They urged the group to confront social questions – often leaning towards socialism or even communism. Unsurprisingly, this created tensions with the leadership of the Kameraden, who feared parental backlash and rejected overt political engagement. In 1927, the Schwarzer Haufen was expelled from the league, and the group formally disbanded a year later. Nonetheless, a few small cells remained active into 1929. It was a short-lived movement, but one that helped shape Litten’s radical political identity.

Litten is best known for bringing Hitler to court. What led to this?

In November 1930, SA men attacked a left-wing dance event at the Edenpalast in Berlin’s Charlottenburg district, seriously injuring several workers. It wasn’t an isolated incident. That summer, the SA had begun establishing themselves in working-class and anti-fascist areas of Berlin, looking for confrontation. Following the NSDAP’s strong showing in the September 1930 Reichstag elections, the SA intensified its campaign to ‘conquer’ these neighbourhoods.

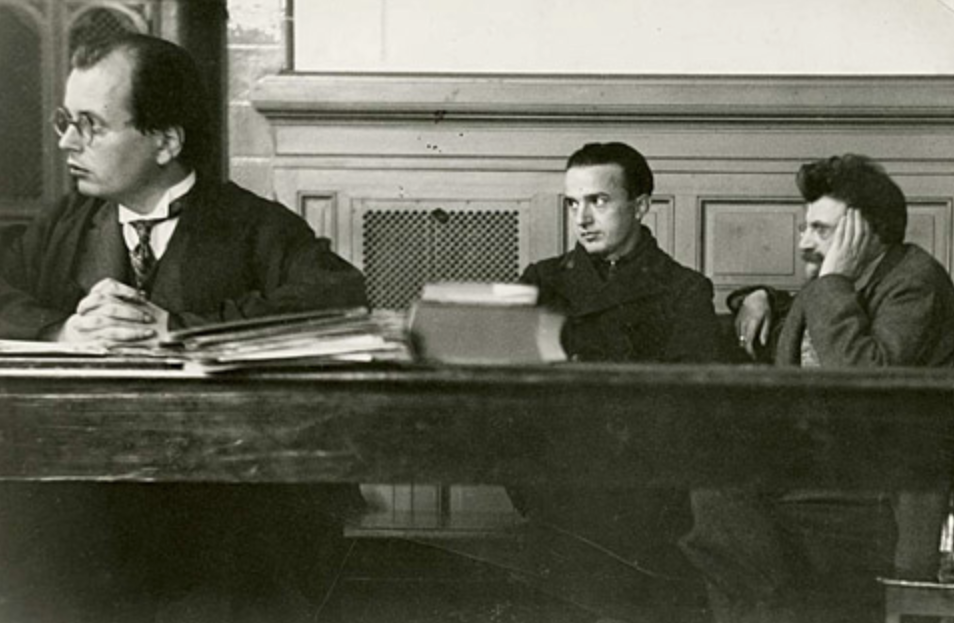

The Edenpalast assault quickly became a high-profile case. Complicating matters, Hitler had only recently sworn an oath of legality in the so-called Ulm Reichswehr Trial, publicly committing the Nazi Party to pursue power by legal means. When Litten summoned Hitler as a witness during the Edenpalast Trial in May 1931, he intended to test that claim – and expose the gap between the party’s rhetoric and the violent actions of its paramilitary wing. By pressing Hitler under cross-examination, Litten highlighted internal contradictions within the Nazi movement – particularly tensions over the SA’s role. The trial drew widespread media attention and made Litten a marked man in Nazi eyes.

Who did Litten work with? How was he organised?

Litten practised law alongside Ludwig Barbasch, a radical socialist and council communist who had been active since the November Revolution of 1918. Their firm took on a wide range of political defence cases, many of them referred by Rote Hilfe (Red Aid), an organisation linked to the Communist Party that provided support to left-wing defendants and prisoners.

The firm was, in some ways, a close-knit community. Barbasch’s father was also involved, as was Margot Fürst – Max Fürst’s wife – who helped manage the office. They all lived together in a shared flat on Koblankstraße, near Berlin’s Volksbühne theatre. It was a living arrangement that reflected their politics: collective, egalitarian, and grounded in shared purpose.

How was Litten’s anti-fascist work perceived at the time?

Litten was already a well-known figure within the Kameraden youth league, and by the time he moved to Berlin, his reputation had preceded him. He contributed to Die Schwarze Fahne, the anarchist newspaper edited by Ernst Friedrich, and worked with Max and Margot Fürst to open a youth counselling centre. His legal work, especially his involvement in politically charged trials – such as the attempt to prosecute Gustav Noske and Karl Zörgiebel, and his role in the tribunal investigating the events of May 1929 – attracted considerable public attention. The Edenpalast Trial, above all, brought him widespread visibility in the press across the political spectrum.

Litten is celebrated as a hero today, but he was never a member of the Communist Party. What were his political views?

There is some debate about this. He may have briefly joined the Communist Party around 1923 or 1924, but if so, he soon left. Some have described him as an anarchist, though that label doesn’t quite fit either. Litten moved in the political space between radical socialism, anarchism, and communism, without ever aligning fully with any single ideology. In any case, politics was just one facet of his personality. Emil Carlebach, a fellow prisoner in Dachau and a committed communist, recalled being startled when Litten spoke to him about ‘angelic beings’ – a comment that challenged the conventional image of Litten as the resolute anti-fascist.

Looking back, Litten is often seen as someone with a disregard for death. Are there accounts of doubts or fears alongside his selflessness?

Margot Fürst recalled that he was not without fear. Whether ‘disregard for death’ is the right phrase is uncertain. He was motivated above all by a sense of justice, a conviction that he had to act – despite the increasing danger, and even when escape was still possible. Nor was he alone in choosing to stay and resist the Nazi regime, at least at first. But it soon became clear that such resistance was futile. Even hardened anti-fascist street fighters were overwhelmed by the scale and brutality of Nazi violence.

As a lawyer and a well-known enemy of the regime, Litten was subject to especially harsh treatment. Early suicide attempts offer some insight into his despair. A rescue attempt in December 1933 – organised by the Fürsts and Felix Hohl – may have been his last real chance of escape. By the time he had endured Buchenwald and arrived in Dachau, he knew there was no hope left. Still, despite the fear and hopelessness, there were moments of solidarity among the prisoners, educational work for younger inmates, and, if only faintly, a glimmer of hope.

What impressed you most about Litten?

My understanding of Litten was shaped above all by those who knew him – Margot Fürst, Birute (Mop) Stern (Fürst), and Nati Steinberger. Even Mop, who was only a child when he died, remembered him vividly. I’ve always admired his courage and moral consistency. But reading his letters from the youth movement, I also saw his capacity for harshness, especially in how he criticised those he disagreed with. Our aim in writing the biography was never to present a heroic epic, but to portray a complex individual in all his contradictions. That complexity is often lost in portrayals that focus solely on the Edenpalast Trial. And yet, that too is part of his legacy.

This article is part of the series Civil Engagement and Democracy in German History: Jewish Experiences and Perspectives, first published in German as Engagement & Demokratie in der jüdisch-deutschen Geschichte by the Freunde und Förderer des Leo Baeck Instituts: https://fuf-leobaeck.de/2025/05/hans-litten-radikaler-kaempfer-gegen-den-hitlerfaschismus/.